Eighteen years before the First World War had begun, Kippax miners were caught up in the second worst disaster in West Yorkshire’s history, at the Peckfield Colliery, Micklefield. On Thursday 30th April 1896, shortly after the men had arrived for work, a miner on the far East side of the mine walked passed the No.1 Gate beyond the fresh air current with his candle. A slight fall in the roof which was not apparent when the Night Deputy inspected the mine had occurred, and a small quantity of firedamp gas had escaped from the roof and was ignited by the man’s candle, killing him instantly. The flame of the explosion reacted with the coal dust, prompting further coal dust to be loosened from the roofs, sides and props, and a violent explosion was generated, plus two secondary explosions. 63 men and boys, plus 19 pit ponies were killed in the explosions, and by the afterdamp gas which was subsequently released:

For those who survived or witnessed the terrible events of this day, it is noticeable that they seemed better prepared and ready to accept the horrors of the First World War, and were eager to serve in whatever capacity they could. There are several references to this disaster within the displays, from Francis Edwards who was killed, to William Bellerby who was Treasurer of the Kippax Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Comforts Fund. Here are a few more links between the 1896 disaster and the First World War, including the remarkable story of Fielding Pickard, who survived both.

George Carter Cawood (1865-1939)

was living at 13 East View, Micklefield in 1896 when he survived the Peckfield Colliery Disaster on 30th April 1896. He was originally reported to be amongst the deceased. This was because he’d gone straight back down the mine to help the rescue efforts once he himself had been rescued, along with his brother Arthur. For a second time, he had to be helped from the mine, suffering the effects of afterdamp poisoning. On the 1st May, he went back down the mine at 5:30am with 5 other rescuers, finding and recovering 5 bodies, before being treated for afterdamp poisoning for a third time. George left mining, moved to Kippax, and ran the Swan Inn. His daughter, Emma Cawood (1893-1977) married Allan Eastwood on the 3rd May 1916, with Allan serving in the First World War, and both their children, Francis Eastwood and Stanley Eastwood serving in the Second World War. George himself was a prominent fund raiser and activist during the First World War in Kippax.

Dr. John Scott Haldane (1860-1936)

Another man in attendance at the Peckfield Colliery disaster was Dr. John Scott Haldane (pictured below), who assisted in the rescue attempts, and tried unsuccessfully to revive one miner who was brought out of the pit over two days later:

Dr. Haldane was frequently in attendance at mining disasters, as his principal area of research was in the effect of gases upon the human body, writing papers upon what he found at such disasters to the Home Office. Upon his advice after the Peckfield disaster, canaries and mice were introduced to the mines to detect early warning signs of carbon monoxide gas. He also designed early respirators for rescue workers. He tested his hypothesies upon himself, by standing in sealed chambers and breathing in different gases to record their effects. He also used his son in these experiments.

During the First World War, Dr. Haldane was sent with a colleague to the front line, at the request of Lord Kitchener, to test the types of gas being used by the Germans. Using his research, Dr. Haldane created a prototype for the first gas masks which were used in combat to counter the use of gas warfare.

Dr. Haldane’s brother, Richard Burdon Haldane (30th July 1856 – 19th August 1928, pictured below) was the Secretary of State for War under Herbert Henry Asquith’s pre-War government, and under the Haldane Reforms for the Army, he re-organised the set up of the Army to prepare for re-enforcements in the event of a major conflict. These reforms were put to the test from August 1914, when the Expeditionary Force was quickly sent to the Continent in World War One, whilst the Territorial Force and Reserves were mobilised as planned to provide a second line of attack. At the beginning of the War, Sir Richard Haldane was the Lord Chancellor.

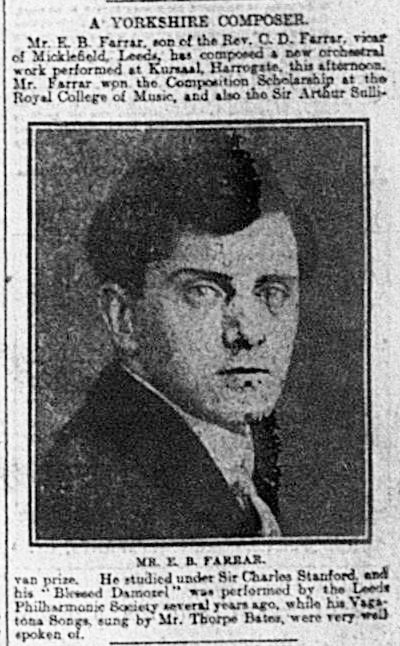

Ernest Bristow Farrar (1885-1918)

Aged 10 at the time of the Peckfield Disaster, Ernest Bristow Farrar was the son of Rev. Charles Druce Farrar who had been Vicar of Micklefied Church since 1887. Rev. C.D. Farrar performed the ceremonies at the funerals of most of the Micklefield miners who had been killed. After Ernest left Leeds Grammar School in 1903, he returned to his father’s church, and was the organist there for two years. The stool upon which he played is still there. He went on to study with Sir Charles Stanford, and was friends with a fellow pupil, Ralph Vaughan-Williams. He married in January 1913, with another composer, Ernest Bullock as his best man. Ernest went on to teach pupils of his own, including Gerald Finizi. Enlisting in 1915, Ernest was promoted to Second Lieutenant of the 3rd Battalion Devonshire Regiment on 27th February 1918. On 3rd July, he came back home to conduct his final piece, Heroic Elegy, before returning to France on the 6th September. After meeting a fellow officer in the Devonshire Regiment, author J.B. Priestley on the front line, Ernest was killed at the Battle of Epehy Ronssoy, near Le Cateau, Cambrai on the 18th September 1918. Priestley, who was wounded in the same Battle, wrote from hospital to Ernest’s widow Olive: “Your husband was to me a representative of one of the finest types of humanity, a creative artist freed from all little meannesses and jealousies. It was a privilege to know him.”